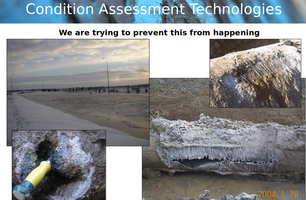

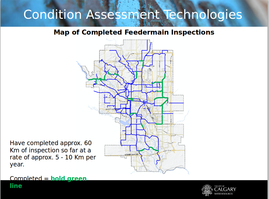

We gave so many presentations on that program to other cities that were following along in our wake. I was able to do this whole section is just slides taken from presentations between 2007 to 2014. This is the title slide from 2014.

We gave so many presentations on that program to other cities that were following along in our wake. I was able to do this whole section is just slides taken from presentations between 2007 to 2014. This is the title slide from 2014.

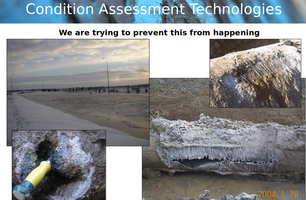

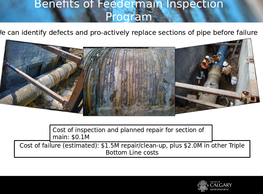

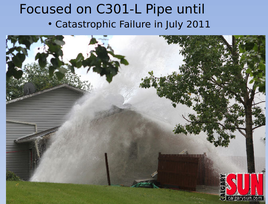

It was the very first time a large main had ever failed in Calgary; we'd started to regard them as simply bullet-proof. A colleague asked me in 2003 why we were inspecting small mains, but not large ones. I told him none had ever broken, so there was no budget. But that a single break would immediately hand us a million a year.

This guy's shivering got us a nearly blank cheque.

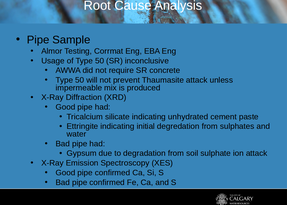

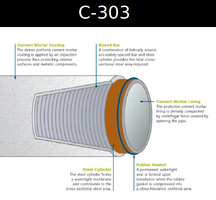

The upshot is that everything depends on the thin steel can made strong by a wire wrap. The cement mortar just holds the wires tight and protects them.

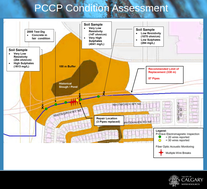

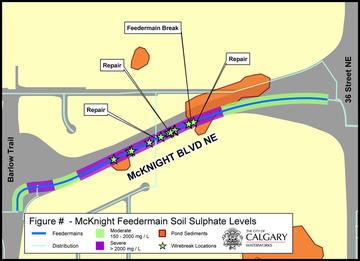

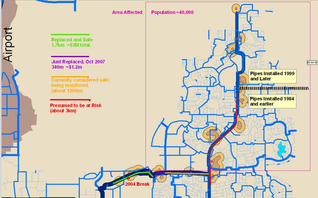

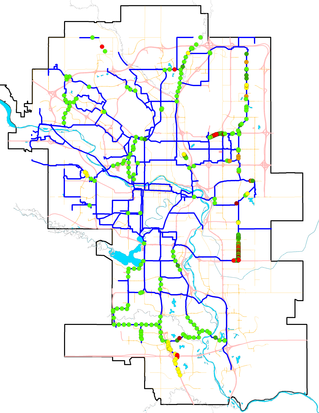

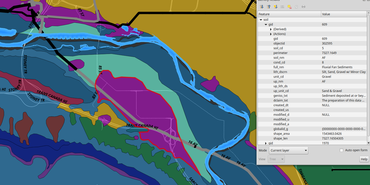

Do note that "historical slough/pond" brown polygon, and the orange 100m buffer zone the GIS drew around it. The bad main, only where high-sulfate soils were, ran from one of those soil-map polygons to another, and stopped.

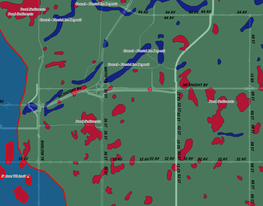

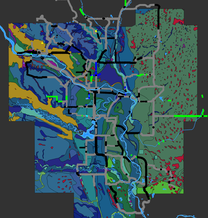

The whole northeast of Calgary, this big flat plain far from our hills, was lousy with swamps and ponds and life..and sulfates.

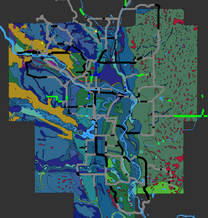

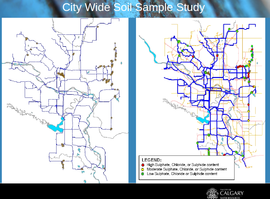

Note the deep blue colour for the soil polygons that are "Fluvial Gravel", that is, river gravels way up on a hill, because Calgary was put through multiple mix-master passes by glaciers that put every soil everywhere.

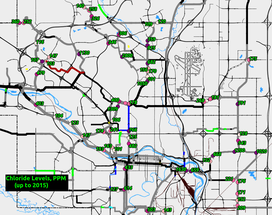

I coloured the GIS soil layer so that the larger the particle size, from clay to silt to sand to gravel, the cooler a colour. Very general rule, the larger the particles, the less corrosive. And extra-corrosive soils, the pond sediments, I made red hot.

The general green all around the gravel and pond sediment blobs is called "Crossfield Till", about equal parts of sand and silt and gravel, and not very corrosive; we didn't have to inspect everywhere - not immediately.

The orangey-yellows are silts and some clays that can be fairly corrosive to my little metal mains, but big concrete pipes, not so bad as the hot-soils of pond bottoms.

I'll come back to this map, and the spot I do wish we'd looked at harder at. But the main message from this is obvious: only an idiot would have spent millions per year, to inspect just ten or twelve kilometres of main per winter, anywhere but in the red freckles of doom all speckled over the east side of the city.

So that's where we started.

Pipeline inspection for oil and gas was a few decades old by then, much easier to budget for when the product is a hundred dollars a barrel, whereas water is just pennies per barrel - and doesn't poison nearly all life it touches.

These folks market in water was basically limited, at the time, to cities that had just recently had a major disaster, like the one in Annapolis, Maryland in 2004 that had cars getting washed down the street.

Even they were impressed at a new customer that wanted, not a frantic inspection of one pipe, but a whole new program to eventually tour the city. We were thinking of that from the start, got a lot of praise for it.

This 2009 slide shows the state of the art, for commercial, reliable work, at the time. The inspections not only required the main to be de-watered, meaning thousands of tonnes of water to be dechlorinated and wasted... they required four guys pushing it along, with eight bike wheels cradling it.

Solving these problems, and automating their solution down to something the device did automatically and independently, was, for the inspection industry, like NASA having to develop astronautics mission by mission. With we early-adopters paying a lot of R&D costs. It was patriotic, for Albertans; the two main companies in the world for pipline inspection were PICA of Edmonton, and Pure Technologies, of Calgary.

This 2009 presentation is our first to mention the eventual fully-submerged submarine inspection tool, the DipeDiver, then starting development.

We were one of several cities with real yearly programs ongoing, that were hauling those prices down by funding the development of better and better tools.

All you got was an SD chip with hours of sound recordings on it, and you'd listen for the hiss of a leak - have, from the time, the approximate location. But we roughly "inspected" over 20 kilometres of main that went clear to Cochrane in a day.

Steel mains are entirely different in failure: just a leak at first, smaller than a dime, and audible. Parenthetically, I predict a bright future for steel feedermain sales in Calgary in future. Maybe for generations.

This 2009 slide shows all those "Pond Sediment" polygons, removed from the rest of the soil map, where they were within a few hundred metres of any large main, at left.

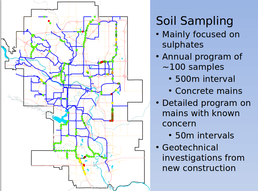

This informed the soil testing program, that's the cheapest thing we could do across hundreds of kilometres of mains. You augur down a few metres and grab a bag of soil, send it to a lab. Event that, I'm afraid, costs a thousand bucks a sample.

Mostly,we had the type that failed on McKnight, C-301-L, which is very similar, but has slightly thicker steel wires, under less stress.

The problem with beating us up over that paper, is that I can find you a paper like that, for nearly every pipe-type ever sold. They all did badly, sometime, somewhere. One paper, I wrote, about ductile iron, trashing its performance in favour of PVC plastic. So I was surprised to come to Vancouver 15 years later,and find ductile iron still in use. Calgary, Winnipeg, other prairie cities with black soils now hate ductile iron, but rocky, non-corrosive Vancouver never saw the problem. The pipe that works so well in Calgary, is PVC plastic - but you can find papers from Australia about how brittle PVC was, how badly it worked in their swelling clay soils. Turned out that Australian factories were using a more-brittle formulation, and putting it in the worst soils for that problem.

We had cut across a private lot, decades before, with a main that served the Rundle community. Whether the proximity to a concrete foundation, or pipes, or wires nearby, was the cause, the pipe picked that one spot on private property to really explode - and tear apart his garage.

The Calgary Sun had a great day, we did not.

C-301-L and C-303, the bar-wrapped pipe, were equally on the agenda, but there were other issues with inspecting the one 11km piece of C-301-E.

This slide is from that 2013 presentation that was the last I was involved in, while the feedermains-inspection engineer concluded his portion with the triumphant first trial of the PipeDiver, with its airlock insertion mechanism that cost something like a million to install.

That was a short run under controlled conditions, in a pipe that had been inspected before, with known technology, so we could compare the PipeDiver's accuracy to established baseline.

Over the next few years, before I left, they progressed to about to start the first PipeDiver commercial inspection, I think in 2016.

Any hope of doing something to a 2-metre diameter main, 11 kilometres long, was years in the future - like SpaceX doesn't plan a Mars mission with their first rocket.

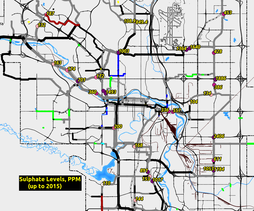

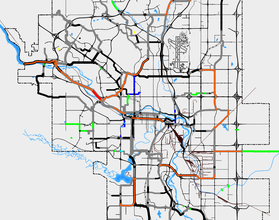

Looking again at the full city map, you see mostly cold soils on the west side of town. But, simplified down to silt and clay soils being warmer colours, there's one chunk of it - right on the Bearspaw South Feeder.

Oh. Em. Gee. Did I miss something? But if I did, how did everybody else miss it for years after I left?

The were tests run in 2014, and they weren't alarming, within range of expectations anywhere in Calgary that wasn't pond sediments. Look around the rest of the map, and you see sulphate numbers up around 1000 and 2000, over in the freckled east, and even one 1493, just a half-kilometre north on Crowchild.

But the sulphates on the south feeder itself are all non-scary, down in the low hundreds.

Scary is about the same number for any kind of corrosive ion: as you get past a thousand parts per million, get worried. There are some high numbers around town, here and there: 2800 north of Nose Hill park, 1200 and 1020 around 52nd St east...but nothing over 500 on those dozen tests done down by the river.

I just can't find fault with holding the priority on it down low..

...and, of course, because the first PipeDiver full test in that very year made the idea even thinkable.

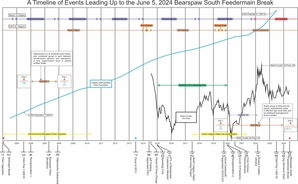

As you may have heard, the Mars Landing of Pipe Diver inspections, the Big Kahuna at last, the inspection of the Bearspaw South Feeder, was planned for October, 2024 - this week, in ironic fact.

I should mention something that Hugh gigged me on - I told Don Braid of The Herald that the pipe was shut down in 2007, when the whole Bearspaw plant was being renovated in that winter.

Braid apparently repeated my misinformation on National TV when Hugh was watching, and Hugh blanched.

As Hugh commented, we not only didn't inspect that main in 2007, we couldn't have; indeed, we had to trust it to run backwards.

So, summing up, I think that City staff are going to do all right in the upcoming inquiry. We were doing more than most cities were, or even could do, to avoid this. And they nearly made it.

The fault that can be found, comes in with how critical and irreplaceable that main was allowed to become, when there had been earlier plans to reinforce that part of the system with more resilience.

It was cancelled in 2021, when it should have been complete by the end of 2022 at latest.

Let's start with that catastrophic fall in the price of oil in 2014, when Mohammed bin Salman of Saudi Arabia, ably assisted by the rest of OPEC, and by Vladimir Putin, not wanting to lose revenue, also opening taps, when bin Salman tried to drive the American frackers broke.

Herald columnists later seemed to blame the layoffs and cancelled projects in the oil industry on either Trudeau, or Notley, or both, though both were not elected for over a year after the price fell, and the cuts started.

It wasn't just industry - Hugh notes that $660M in public projects were cancelled over the next five years, even though the price of oil began to recover after less than 18 months. It was a bit of a jobless recovery, you see, and they were driven by population growth, which they continued to imagine would crater, even as Hugh's blue line shows Calgary growth steadily proceeding apace, without oil to drive it. The growth-predictors at the very top of the city, the people estimating needs for water, roads, buildings, everything, still believed that 2014 had been the end of the world, somehow. But even 2020 didn't slow it down; in fact, growth took off in 2022.

But how could they know? Hugh discovered that in 2019, they quit using the census data. 2020 didn't even have a census, but they didn't start using it again in 2021 or 2022.

We heard a lot of criticism - actually nothing but - for the huge re-organization started by CEO David Duckworth. As with most of the re-organizations for the last few decades, it seemed to take away people who knew a subject area, from their subject area, and moved in more of the "professional manager class" who mainly know how to manage people - and budgets.

There was a new head of all "Infrastructure Delivery", Michael Thompson, who led all infrastructure projects from any department, and we suspect it was pressure from that high up that made Water cancel the North Calgary Water Servicing Project, after 3 years of work that included some $5M in engineering design and planning. Water projects managers were ready to pull the trigger and break ground, when the plug was pulled instead.

Meanwhile, it wasn't just Calgary that jumps into accelerated growth at the end of Hugh's timeline: so had Airdrie, which we service from that Beddington reservoir, and Chestermere, served by a main running out east from the Glenmore zone.

They planned as if for little or no growth, continued with that plan as growth obviously continued, right through 2018 and 2019. And then there was a growth spurt. All that growth made the Bearspaw South Feeder particularly devastating.