My presentation tonight is partly about my keen new computer, which I think is the appearance of a new product category in information appliances, and partly my personal opinion about the appearance of these categories, from the mainframe through minicomputer to workstations, PCs and these. Moore's Law isn't just about increasing returns for the same dollar: it's about spending fewer dollars at all.

My presentation tonight is partly about my keen new computer, which I think is the appearance of a new product category in information appliances, and partly my personal opinion about the appearance of these categories, from the mainframe through minicomputer to workstations, PCs and these. Moore's Law isn't just about increasing returns for the same dollar: it's about spending fewer dollars at all.

fullscreen

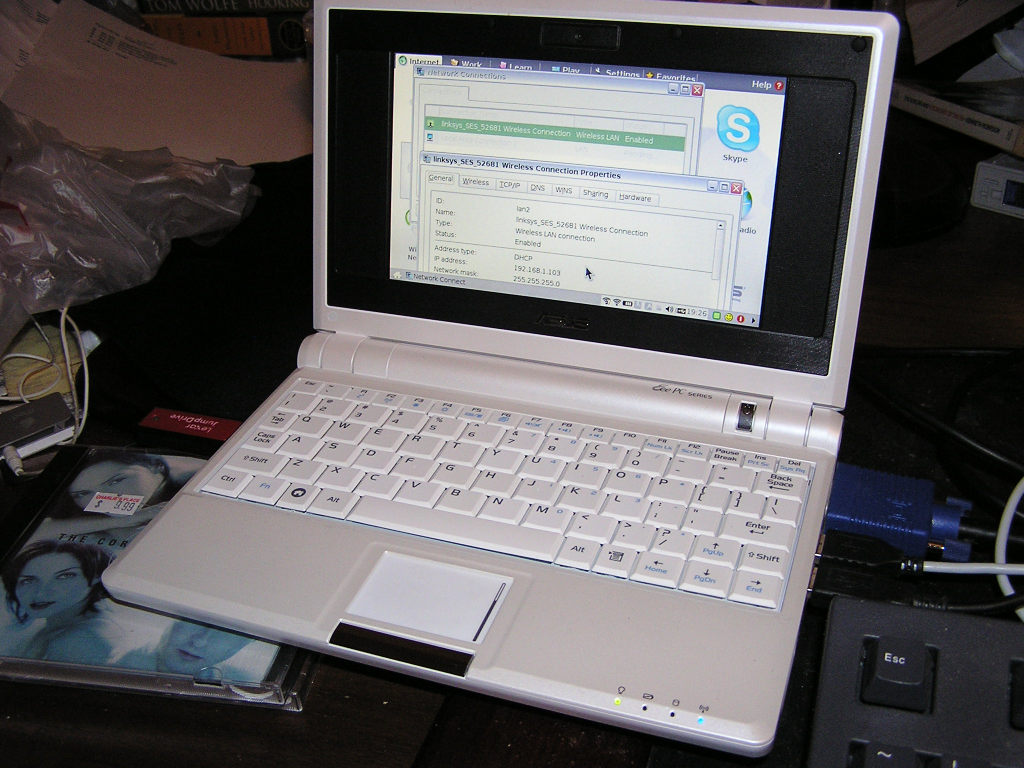

A few weeks ago, I proudly posted this photo of my new ASUS-made "EEE PC", so named by ASUSTEK for it being "Easy to Learn, Easy to Work, Easy to Play". Note that they are selling it on ease-of-use, not on its tiny size. Or perhaps they feel no need to call it the "Eensy-Teensy PC" because that speaks for itself.

A few weeks ago, I proudly posted this photo of my new ASUS-made "EEE PC", so named by ASUSTEK for it being "Easy to Learn, Easy to Work, Easy to Play". Note that they are selling it on ease-of-use, not on its tiny size. Or perhaps they feel no need to call it the "Eensy-Teensy PC" because that speaks for itself.

fullscreen

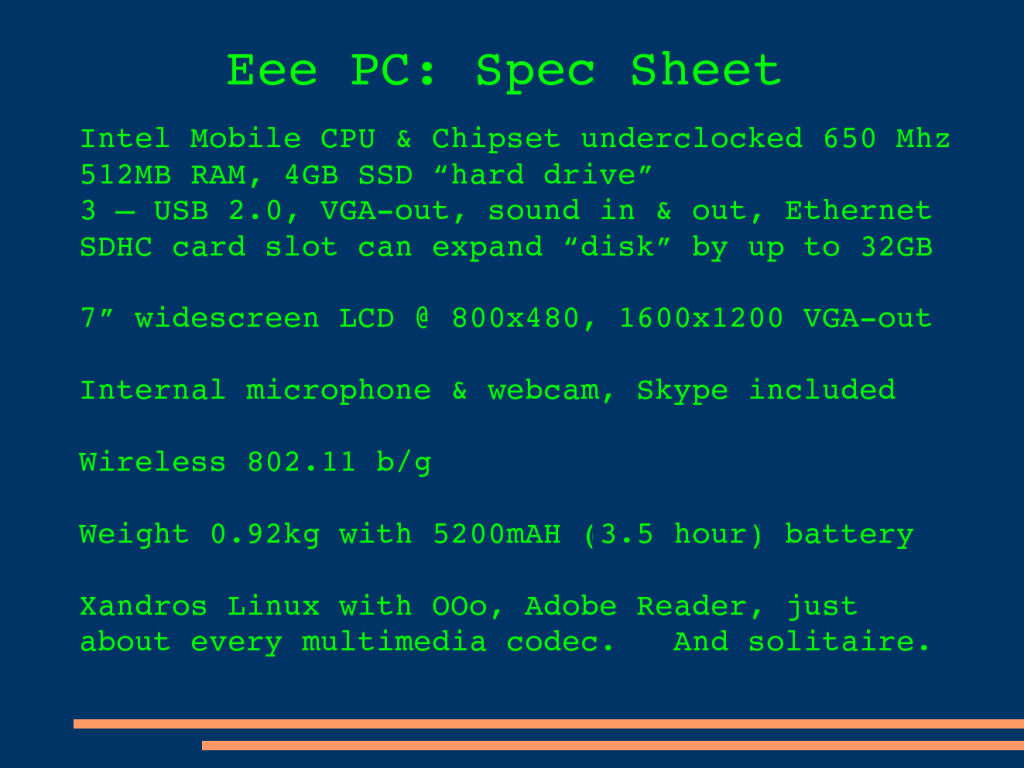

Except for the very small "hard drive" based on flash memory, the specifications for the Eee PC are about those of a common desktop of five to seven years ago. It runs basically all the popular Linux software with reasonable performance. Video playback of AVI files is smooth. Since the USB port now connects you to everything, it can handle a wide variety of peripherals. Like any good modern laptop, all networking is built-in and pre-configured. It is, in short, not a toy.

Except for the very small "hard drive" based on flash memory, the specifications for the Eee PC are about those of a common desktop of five to seven years ago. It runs basically all the popular Linux software with reasonable performance. Video playback of AVI files is smooth. Since the USB port now connects you to everything, it can handle a wide variety of peripherals. Like any good modern laptop, all networking is built-in and pre-configured. It is, in short, not a toy.

fullscreen

Here's one with better photography, it's Hrvoje Lukatela's purchase, beside his beloved Leica camera to emphasize the small size. Mine cost me $400 - or rather $500 after GST and the purchase of a small mouse and a 4GB SD card. It has a 4GB solid-state hard drive, but 2.5GB of that is taken up with Xandros Linux with the ICE window manager, and a fairly full suite of Linux applications including OpenOffice. Xandros is Debian-based, so it was easy to add in the GIMP and a few other favourites they forgot.

Here's one with better photography, it's Hrvoje Lukatela's purchase, beside his beloved Leica camera to emphasize the small size. Mine cost me $400 - or rather $500 after GST and the purchase of a small mouse and a 4GB SD card. It has a 4GB solid-state hard drive, but 2.5GB of that is taken up with Xandros Linux with the ICE window manager, and a fairly full suite of Linux applications including OpenOffice. Xandros is Debian-based, so it was easy to add in the GIMP and a few other favourites they forgot.

fullscreen

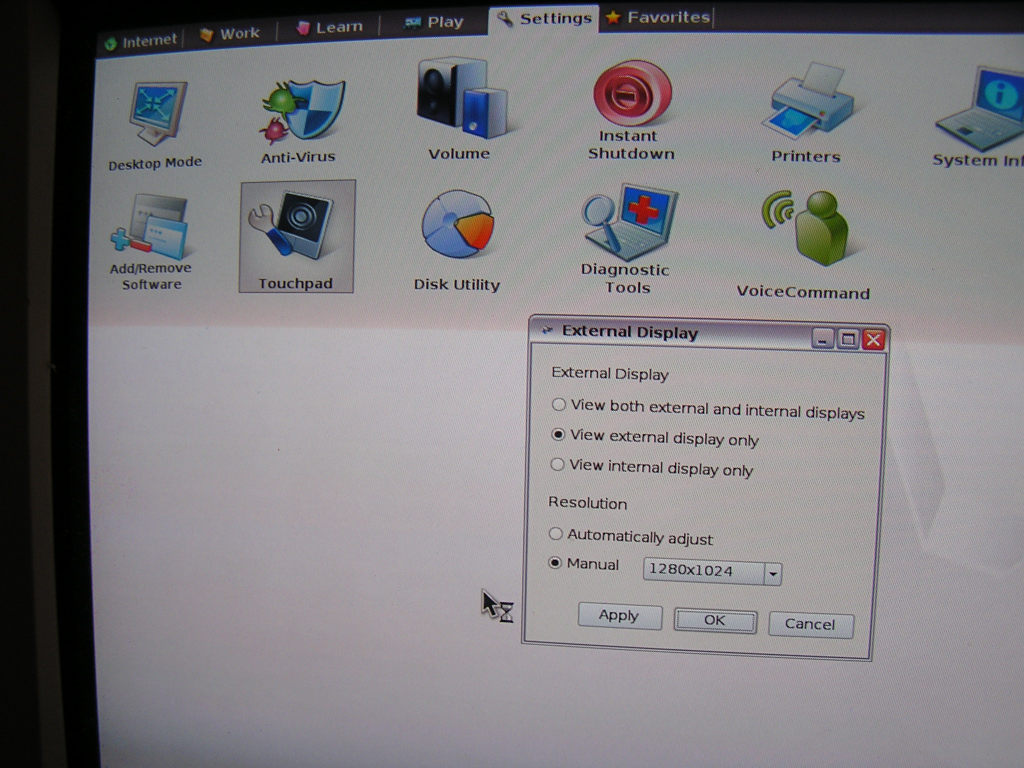

The killer app for me, and I need one since "hey, cool toy" doesn't take me past the $100 line, is that I can give presentations with it. The video port somehow senses the monitor capabilities - on a good monitor, I've had it up to 1600 by 1200 and the graphics response has been decent.

The killer app for me, and I need one since "hey, cool toy" doesn't take me past the $100 line, is that I can give presentations with it. The video port somehow senses the monitor capabilities - on a good monitor, I've had it up to 1600 by 1200 and the graphics response has been decent.

fullscreen

It also responds instantly to having a mouse and keyboard plugged into two of the three USB ports. No waiting, no messages, the machine just starts using them. If booted with an external monitor plugged in, it automatically displays on both, though you'll want to turn it up from the default 800x480 widescreen. It's a very usable machine as a desktop this way, even if only about 650 MHz.

It also responds instantly to having a mouse and keyboard plugged into two of the three USB ports. No waiting, no messages, the machine just starts using them. If booted with an external monitor plugged in, it automatically displays on both, though you'll want to turn it up from the default 800x480 widescreen. It's a very usable machine as a desktop this way, even if only about 650 MHz.

fullscreen

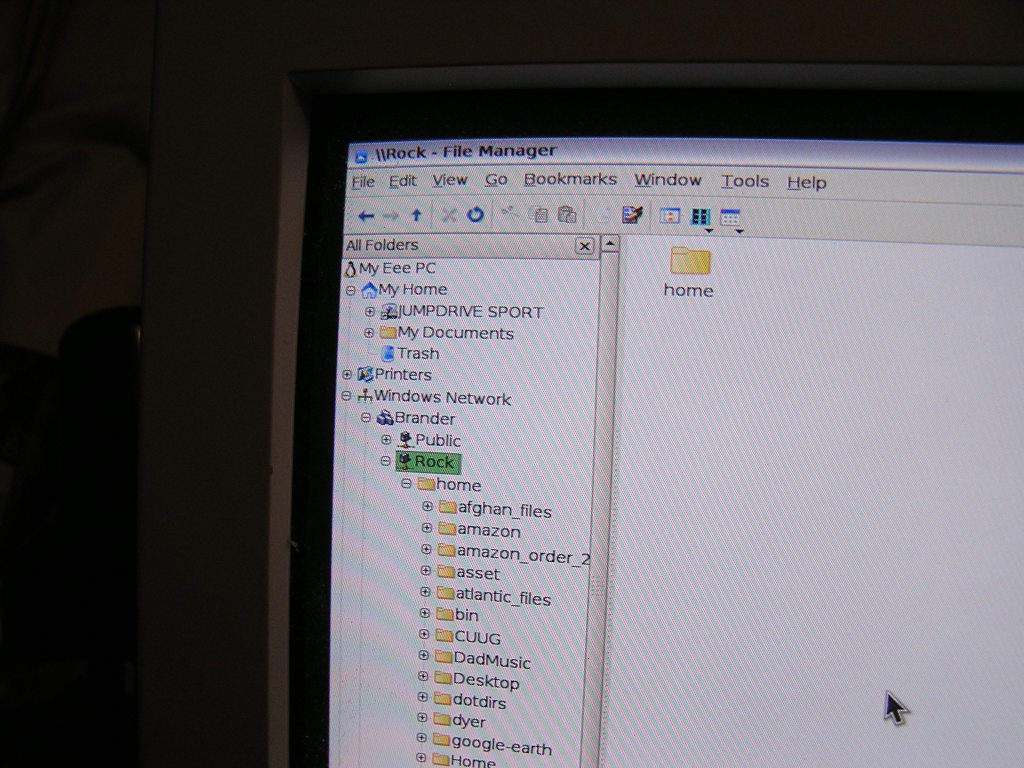

It wouldn't have any killer apps if they were not right about the "Easy to Use" claims. Like my own preferred MEPIS Linux, Xandros has everything a typical workstation user wants, all pre-set up; no config fiddling. Here it's just automatically found my home SMB network after I logged into the home WiFi and I can browse through server files. The WiFi and Ethernet connections have "just worked" everywhere I've tried. So has every USB key and USB-based hard drive I've plugged in, although it can only read my 200GB NTFS drive.

It wouldn't have any killer apps if they were not right about the "Easy to Use" claims. Like my own preferred MEPIS Linux, Xandros has everything a typical workstation user wants, all pre-set up; no config fiddling. Here it's just automatically found my home SMB network after I logged into the home WiFi and I can browse through server files. The WiFi and Ethernet connections have "just worked" everywhere I've tried. So has every USB key and USB-based hard drive I've plugged in, although it can only read my 200GB NTFS drive.

fullscreen

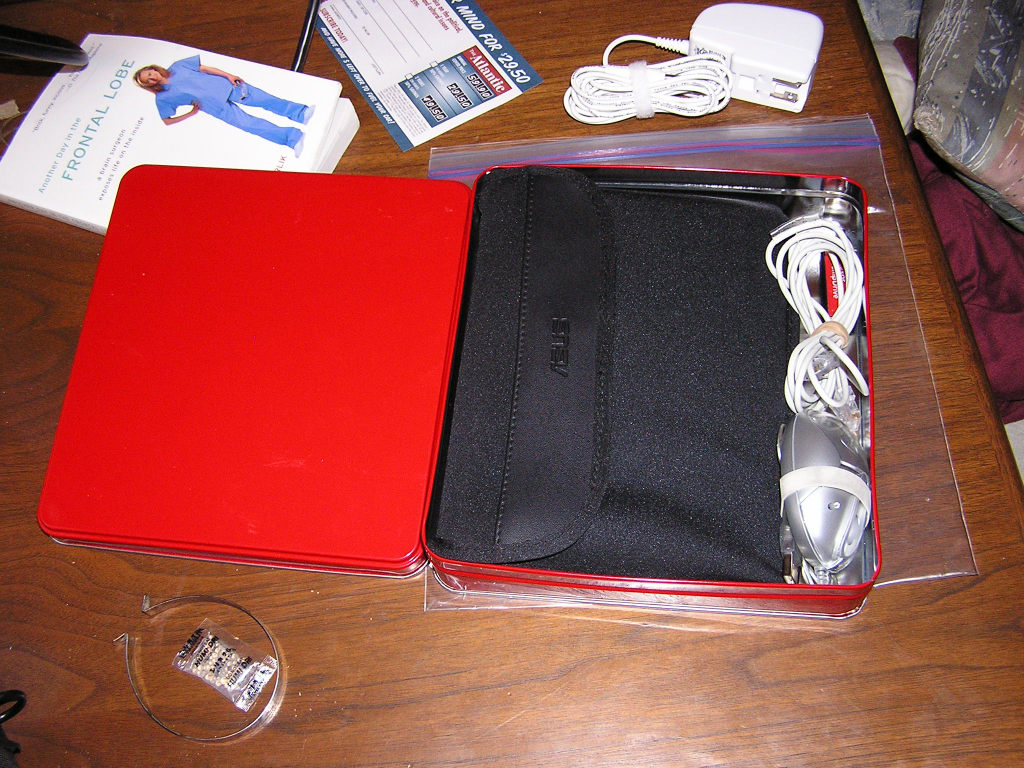

It comes with a neoprene envelope that will protect against scratches and very minor impacts, but I wanted a little more protection without the space and weight of those huge padded laptop cases, and a little space for the minimouse, ethernet cord, etc, for travelling.

It comes with a neoprene envelope that will protect against scratches and very minor impacts, but I wanted a little more protection without the space and weight of those huge padded laptop cases, and a little space for the minimouse, ethernet cord, etc, for travelling.

fullscreen

So I bought an $8 tin of Belgian cookies that it just barely fits in, adding maybe 100g of weight to the kilogram of computer and all equipment. It's still of a size and weight where it's not a decision to throw it in my pack for every day to work or on almost any other trip where there's even a slim chance of needing it.

So I bought an $8 tin of Belgian cookies that it just barely fits in, adding maybe 100g of weight to the kilogram of computer and all equipment. It's still of a size and weight where it's not a decision to throw it in my pack for every day to work or on almost any other trip where there's even a slim chance of needing it.

fullscreen

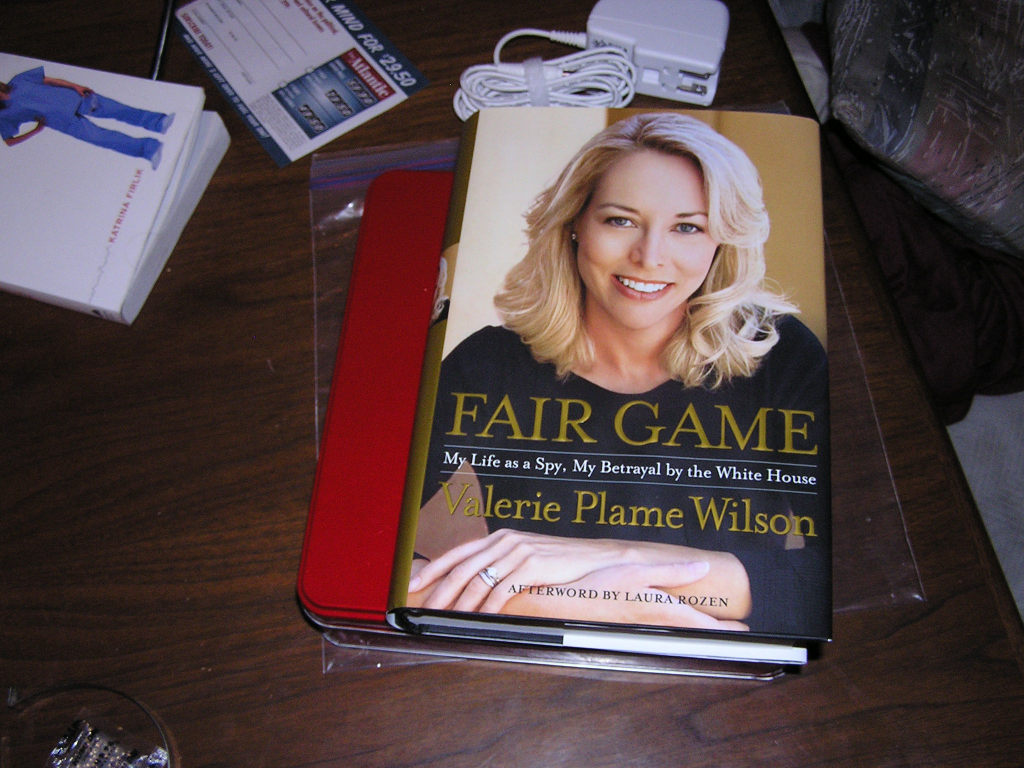

The whole assembly can nearly fit under a hardback book, at least without the fist-size 18W charger; which I don't bring along on daily trips because the battery lasts 3 hours. They just put out a second model, with one hour less battery and no webcam, no built-in microphone, for $349.

The whole assembly can nearly fit under a hardback book, at least without the fist-size 18W charger; which I don't bring along on daily trips because the battery lasts 3 hours. They just put out a second model, with one hour less battery and no webcam, no built-in microphone, for $349.

fullscreen

It turns out that size does matter. I use the old joke because a recent episode of Corner Gas got laughs out of the men in town competing for how small a cell phone they could buy. When the first MP3 players came out nearly 10 years back, we thought the size of a pack of cigarettes was small enough to be killer. But as I went from the $400, 64MB Samsung Yepp at left, through a couple of Lexar Jumpdrive-based machines in the middle, I kept having problems that the designers had tossed in the belt clip as an afterthought. The players tended to bounce off it when you ran and get damaged - or in the case of the Lexars, destroyed.

It turns out that size does matter. I use the old joke because a recent episode of Corner Gas got laughs out of the men in town competing for how small a cell phone they could buy. When the first MP3 players came out nearly 10 years back, we thought the size of a pack of cigarettes was small enough to be killer. But as I went from the $400, 64MB Samsung Yepp at left, through a couple of Lexar Jumpdrive-based machines in the middle, I kept having problems that the designers had tossed in the belt clip as an afterthought. The players tended to bounce off it when you ran and get damaged - or in the case of the Lexars, destroyed.

fullscreen

I finally had to concede that after all these years it's STILL only Apple that really thinks hard about ergonomics. In the case of MP3 players, the iPod shuffle has for me the perfect ergonomics; I have abandoned plans to buy even a nano, because the shuffle has the ultimate ergonomic advantage for its function, the same one as the EEE PC: it's really, really tiny. Combined with the brilliant, cheap, simple ergonomic feature of a clip that can exert force of several times the 30g weight, you can't feel it, it can't fall off any item of clothing, and the only button I hit more than a few times a day, the play/pause, is half the size of the whole unit. Only in heavy ski gloves can you miss it.

I finally had to concede that after all these years it's STILL only Apple that really thinks hard about ergonomics. In the case of MP3 players, the iPod shuffle has for me the perfect ergonomics; I have abandoned plans to buy even a nano, because the shuffle has the ultimate ergonomic advantage for its function, the same one as the EEE PC: it's really, really tiny. Combined with the brilliant, cheap, simple ergonomic feature of a clip that can exert force of several times the 30g weight, you can't feel it, it can't fall off any item of clothing, and the only button I hit more than a few times a day, the play/pause, is half the size of the whole unit. Only in heavy ski gloves can you miss it.

fullscreen

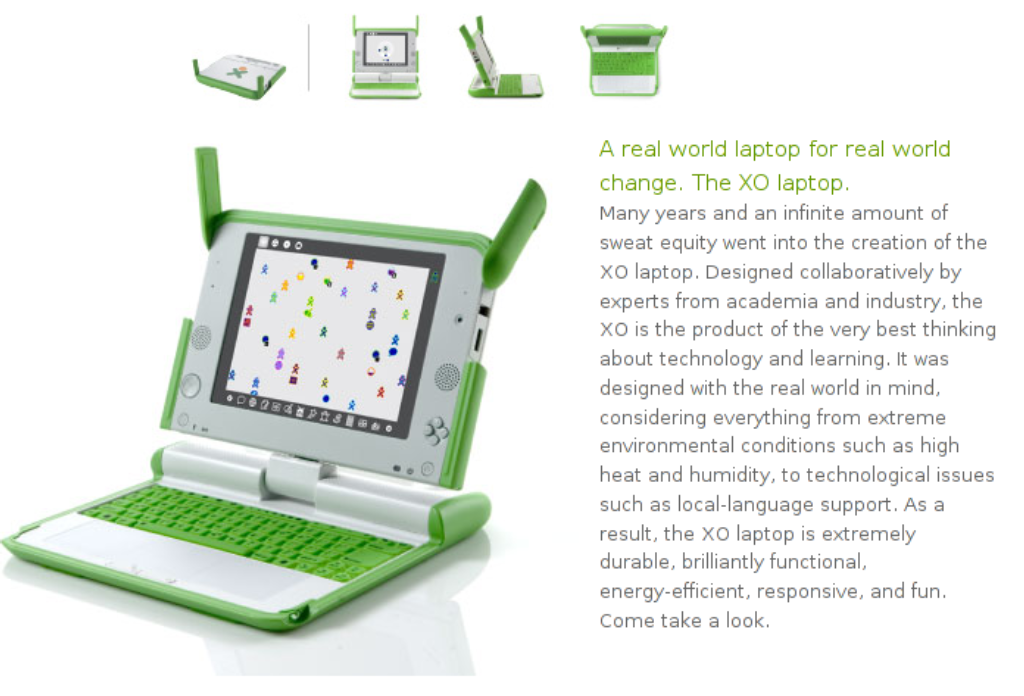

The iPod demonstrates the power of an idea. Everybody else has access to the same technology as Apple, generally - Apple just has an enviable track record of turning those possiblities into products that match needs. The EEE PC and some other product like it very likely owe their existence to an idea out of the MIT Media Lab, another very bright bunch that wake up in the morning thinking ergonomics, ergonomics, ergonomics. Nicholas Negroponte, their director, started pushing this idea a few years back: the XO laptop, for the "One Laptop Per Child" project, also nicknamed the "$100 laptop". It was a bad nickname since they were then crapped on for coming in at $188 for the first models. They should have called it the "under $200 laptop" for coverage - and because $200 is definitely a magic figure, as I will go on to discuss.

The iPod demonstrates the power of an idea. Everybody else has access to the same technology as Apple, generally - Apple just has an enviable track record of turning those possiblities into products that match needs. The EEE PC and some other product like it very likely owe their existence to an idea out of the MIT Media Lab, another very bright bunch that wake up in the morning thinking ergonomics, ergonomics, ergonomics. Nicholas Negroponte, their director, started pushing this idea a few years back: the XO laptop, for the "One Laptop Per Child" project, also nicknamed the "$100 laptop". It was a bad nickname since they were then crapped on for coming in at $188 for the first models. They should have called it the "under $200 laptop" for coverage - and because $200 is definitely a magic figure, as I will go on to discuss.

fullscreen

The "Frankly Speaking" column by Frank Hayes in this month's Computerworld is about the Gphone idea changing the whole phone game whether the product itself succceeds or not. His example for how that works was the XO laptop followed by the EEE PC, and the Intel Classmate.

The "Frankly Speaking" column by Frank Hayes in this month's Computerworld is about the Gphone idea changing the whole phone game whether the product itself succceeds or not. His example for how that works was the XO laptop followed by the EEE PC, and the Intel Classmate.

fullscreen

As Hayes points out, the XO was sneered at to start with. And it's certainly still unclear whether One Laptop Per Child will revolutionize third-world education. But there's no question that, as Hayes said, the idea itself has taken hold and created a new market segment for the under-$400 laptop, if not under $200.

As Hayes points out, the XO was sneered at to start with. And it's certainly still unclear whether One Laptop Per Child will revolutionize third-world education. But there's no question that, as Hayes said, the idea itself has taken hold and created a new market segment for the under-$400 laptop, if not under $200.

fullscreen

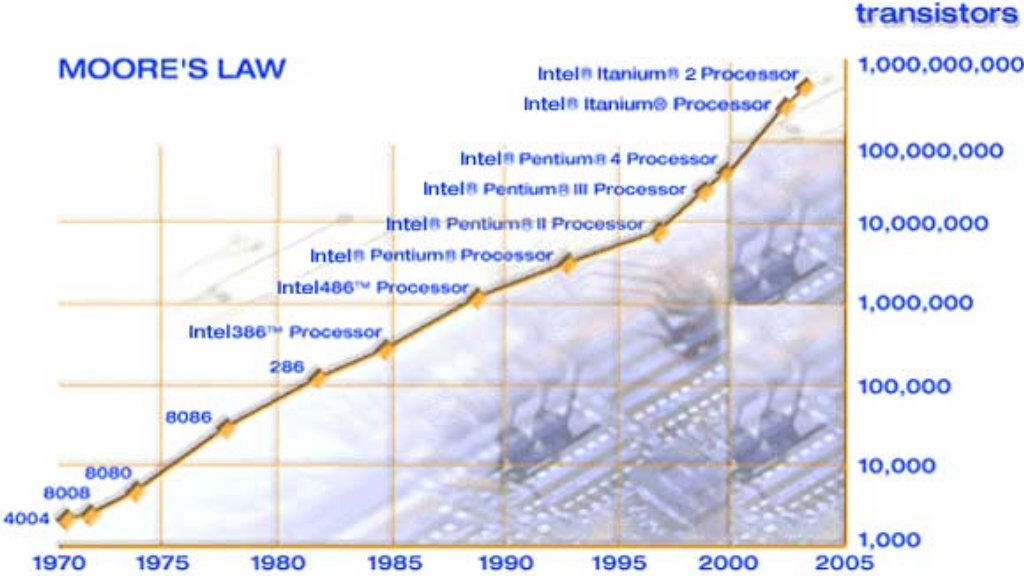

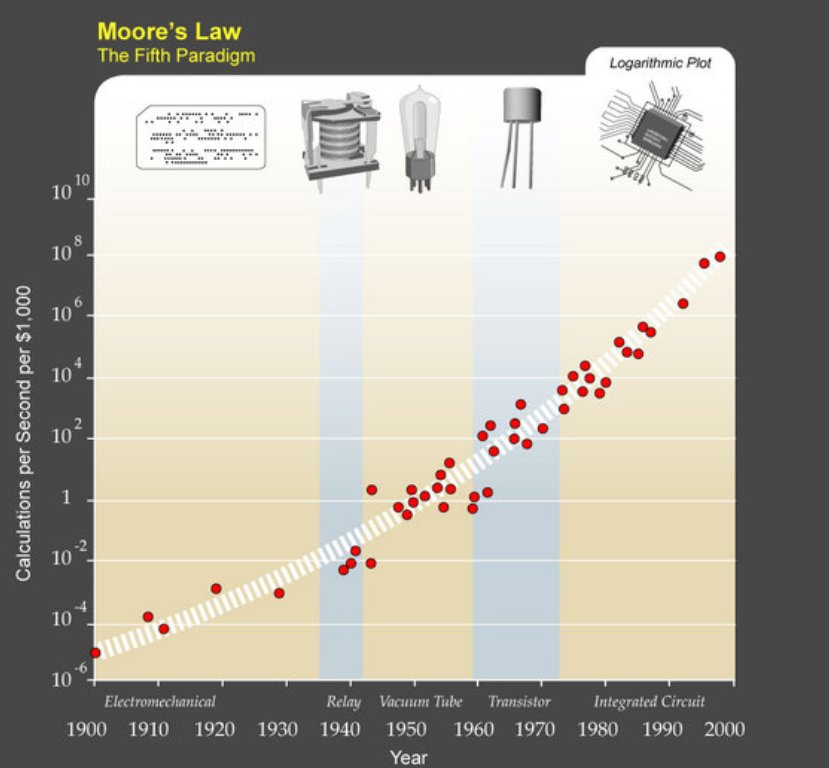

And we've come to the thesis I wanted to put forth tonight, which is that the famous "Law" of Gordon Moore of Intel - shown here with Intel's own chips over a third of a century - has been partly misstated for all that time. Moore originally said that the number of circuit elements per dollar will double every year.

And we've come to the thesis I wanted to put forth tonight, which is that the famous "Law" of Gordon Moore of Intel - shown here with Intel's own chips over a third of a century - has been partly misstated for all that time. Moore originally said that the number of circuit elements per dollar will double every year.

fullscreen

It's not the first exponential improvement in a technology, by the way. This

has been on my CUUG web site since 1995 - an exponential improvement in steam

engine efficiency over 300 years, it doubled every sixty - from 32 pounds of coal per horsepower-hour down to one. James Watt's real fame wasn't inventing the engine, it was jumping ahead 60 years on the curve and making an economic one possible. But nothing beats chips for the number of doublings or their speed.

It's not the first exponential improvement in a technology, by the way. This

has been on my CUUG web site since 1995 - an exponential improvement in steam

engine efficiency over 300 years, it doubled every sixty - from 32 pounds of coal per horsepower-hour down to one. James Watt's real fame wasn't inventing the engine, it was jumping ahead 60 years on the curve and making an economic one possible. But nothing beats chips for the number of doublings or their speed.

fullscreen

The "every year" got changed to "every 18 months" just years later, and now is often stated as "every two years" as the final physical diminishing returns are felt. We're now down to 45 nanometres, and at 30, physicists tell us that electrons will start quantum tunneling between elements no matter how high the resistivity of the substrate. We'll see - since predictions of the Law's death have been often exaggerated. This interesting treatment takes Moore's Law back before electronics to conclude that it holds backwards into the era of electromechanical calculators in 1900.

The "every year" got changed to "every 18 months" just years later, and now is often stated as "every two years" as the final physical diminishing returns are felt. We're now down to 45 nanometres, and at 30, physicists tell us that electrons will start quantum tunneling between elements no matter how high the resistivity of the substrate. We'll see - since predictions of the Law's death have been often exaggerated. This interesting treatment takes Moore's Law back before electronics to conclude that it holds backwards into the era of electromechanical calculators in 1900.

fullscreen

So did this researcher, going back to 1890, concluding it worked with a slightly different function using a double exponential. No matter. It's not a physical law, it's a law of physics combined with engineering combined with economics: these are the information processing products that people were willing to pay enough for that private companies could make payroll and invent a next generation.

So did this researcher, going back to 1890, concluding it worked with a slightly different function using a double exponential. No matter. It's not a physical law, it's a law of physics combined with engineering combined with economics: these are the information processing products that people were willing to pay enough for that private companies could make payroll and invent a next generation.

fullscreen

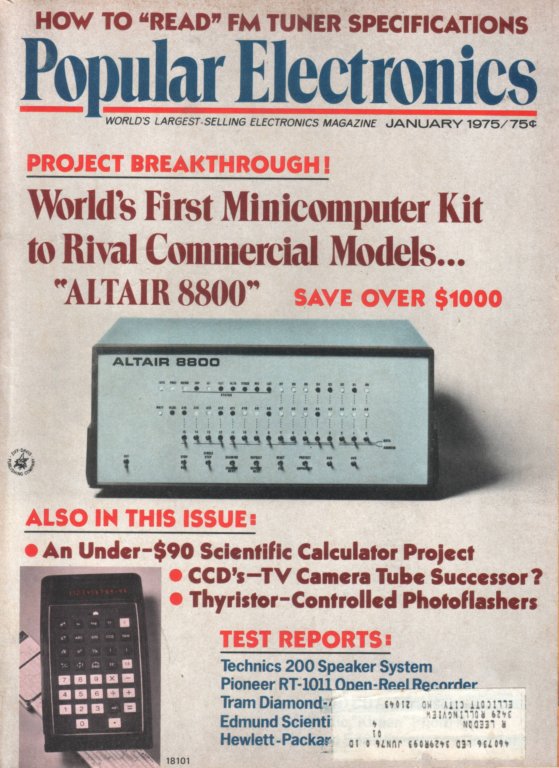

But that begs the question of what people will buy. Moore's Law first caused multimillion-dollar mainframes to go up in power, but it also allowed the invention of the $100,000 DEC minicomputers that went up in power. And that first Intel 4004 chip allowed the invention of this: the MITS Altair, which like my EEE PC also cost $400, for the kit. The 1975 Popular Mechanics issue that featured it is so famous, this image was easy to find on the Net. Mind you, the Altair couldn't do much of any use, and only fanatic hobbyists bought it. Like the OLPC, however, the fanaticism of those buyers - one lived in MITS parking lot for two weeks waiting for his to come off the 3-man assembly line - created a new market category promptly filled by the Apple I and Radio Shack's TRS series.

But that begs the question of what people will buy. Moore's Law first caused multimillion-dollar mainframes to go up in power, but it also allowed the invention of the $100,000 DEC minicomputers that went up in power. And that first Intel 4004 chip allowed the invention of this: the MITS Altair, which like my EEE PC also cost $400, for the kit. The 1975 Popular Mechanics issue that featured it is so famous, this image was easy to find on the Net. Mind you, the Altair couldn't do much of any use, and only fanatic hobbyists bought it. Like the OLPC, however, the fanaticism of those buyers - one lived in MITS parking lot for two weeks waiting for his to come off the 3-man assembly line - created a new market category promptly filled by the Apple I and Radio Shack's TRS series.

fullscreen

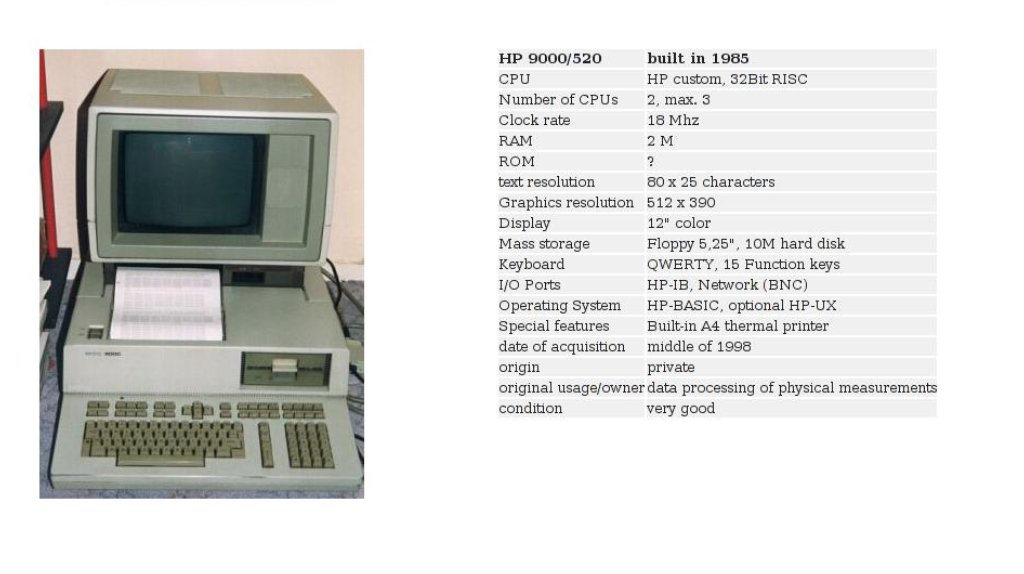

Meanwhile, people who were very much not hobbyists were zeroing in on the order of magnititude between the $100,000 VAX and the $1000 hobby machine; the HP 9000 line of microcomputers all clocked in around $10,000 but gave the working engineer or scientist a machine of similar utility to the VAX terminal.

Meanwhile, people who were very much not hobbyists were zeroing in on the order of magnititude between the $100,000 VAX and the $1000 hobby machine; the HP 9000 line of microcomputers all clocked in around $10,000 but gave the working engineer or scientist a machine of similar utility to the VAX terminal.

fullscreen

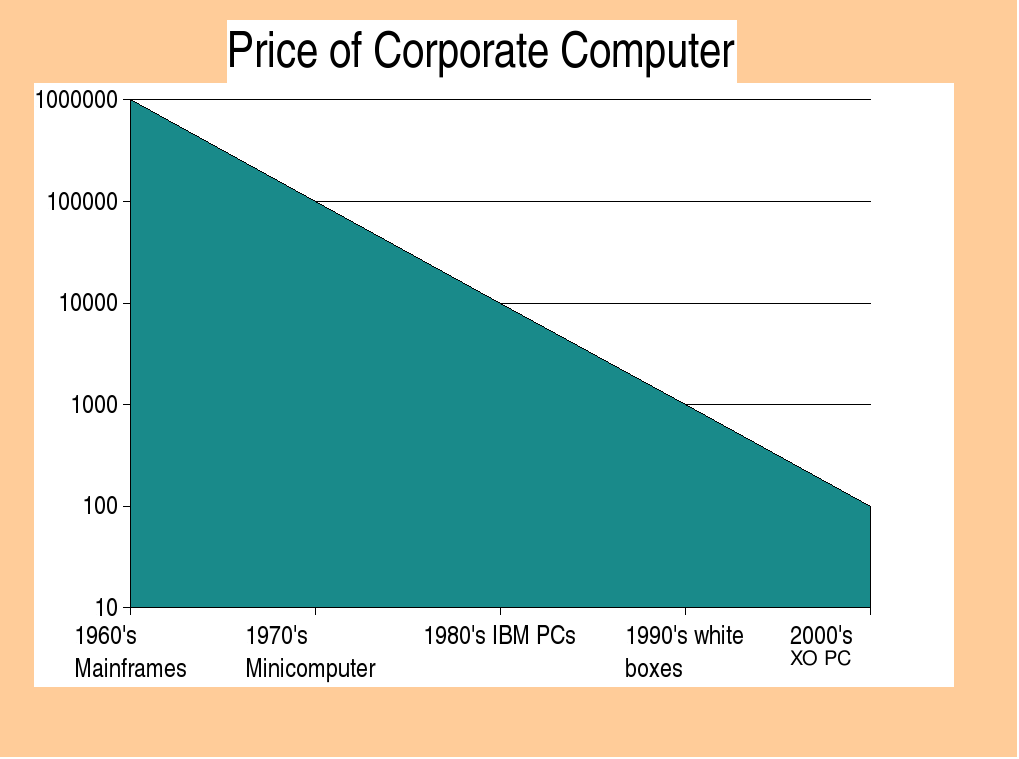

My first re-statement of Moore's was that the real market and sociological effect was to reduce the price of computers by an order of magnitude per decade. Something along the lines of: "it was millions for mainframes in the 60's, hundreds of thousands for PDPs and VAXes in the 70's, tens thousand for early PCs like the HP 9000's, then thousands, now hundreds". It does indicate something about the minimum you had to pay to get some work done, but since they all service different numbers of terminals or had whole different functions, it's basically rubbish.

My first re-statement of Moore's was that the real market and sociological effect was to reduce the price of computers by an order of magnitude per decade. Something along the lines of: "it was millions for mainframes in the 60's, hundreds of thousands for PDPs and VAXes in the 70's, tens thousand for early PCs like the HP 9000's, then thousands, now hundreds". It does indicate something about the minimum you had to pay to get some work done, but since they all service different numbers of terminals or had whole different functions, it's basically rubbish.

fullscreen

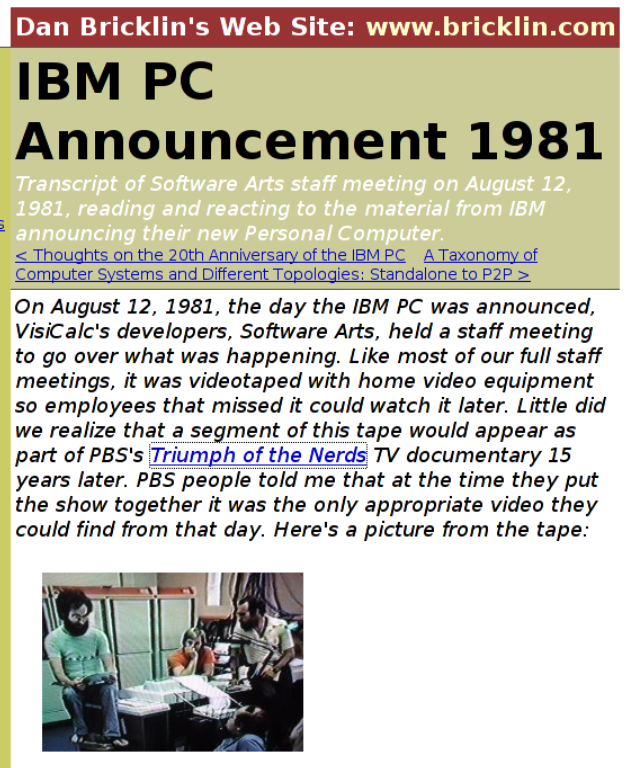

Some consistency may be had by sticking to whatever was the

widely-accepted corporate PC desktop, once there was such a thing.

Dan Bricklin, inventor of the spreadsheet, had a tape running

when he announced to his staff the release of the original IBM PC. It wound

up in the PBS "Triumph of the Nerds" documentary.

He has a transcription at his website.

Some consistency may be had by sticking to whatever was the

widely-accepted corporate PC desktop, once there was such a thing.

Dan Bricklin, inventor of the spreadsheet, had a tape running

when he announced to his staff the release of the original IBM PC. It wound

up in the PBS "Triumph of the Nerds" documentary.

He has a transcription at his website.

fullscreen

As you can see, you could get something useless for $1500,

useful for $3000, and do graphics and printing for $4500 -

which caused the audience to gasp with appreciation. Corporate

buyers, too. So there's a number for 1981.

As you can see, you could get something useless for $1500,

useful for $3000, and do graphics and printing for $4500 -

which caused the audience to gasp with appreciation. Corporate

buyers, too. So there's a number for 1981.

fullscreen

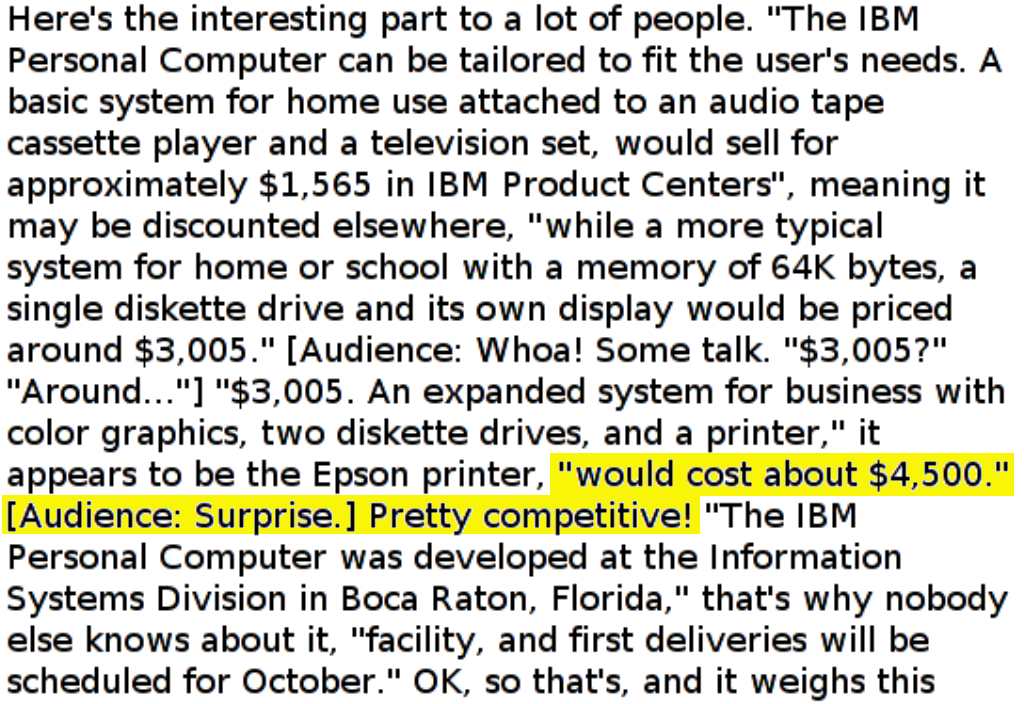

It was down from the $10,000 HP prices of the same time, and the typical price change is more like a halving per decade. I won't dignify that statement with some pseudo-scientific graph, it's only a rule of thumb. The machines being compared are still not really comparable - most things on this slide, from my personal recollections of machines I've bought and machines my employers have bought, are at different function points. The VIC-20 never did anything useful because it had no printer. The original IBM-XT did some great traffic engineering for a U of C professor. The City of Calgary budget at bottom was double what you could do with clone purchase at the time, the price of buying all-IBM with every bell and whistle. A special deviation from the rule was the Commodore 64 in the middle, just $800 base, $1600 by the time you had a disk and printer.

It was down from the $10,000 HP prices of the same time, and the typical price change is more like a halving per decade. I won't dignify that statement with some pseudo-scientific graph, it's only a rule of thumb. The machines being compared are still not really comparable - most things on this slide, from my personal recollections of machines I've bought and machines my employers have bought, are at different function points. The VIC-20 never did anything useful because it had no printer. The original IBM-XT did some great traffic engineering for a U of C professor. The City of Calgary budget at bottom was double what you could do with clone purchase at the time, the price of buying all-IBM with every bell and whistle. A special deviation from the rule was the Commodore 64 in the middle, just $800 base, $1600 by the time you had a disk and printer.

fullscreen

This is from last weekend's CNN Website. The C64 is fondly remembered two decades later by kids who grew up gaming on it, but my brother used it as his sole word processor right through law school, and we did as much traffic engineering on it as I'd done with the PC years earlier, albeit more slowly. The $800, one-piece, simple-to-run C64 is the true ancestor of the XO laptop and the EEE PC.

This is from last weekend's CNN Website. The C64 is fondly remembered two decades later by kids who grew up gaming on it, but my brother used it as his sole word processor right through law school, and we did as much traffic engineering on it as I'd done with the PC years earlier, albeit more slowly. The $800, one-piece, simple-to-run C64 is the true ancestor of the XO laptop and the EEE PC.

fullscreen

And then here's eight years later than that PC and six years later than my

$12,000 fully-decked out XT. The Calgary Computer Paper back page, 1989.

Prices range from just under $2000, to just over $3000, with the at-the-time inevitable conspicuous consumption of the $7000 for the 33MHz machine just a third faster than the $3200 25MHz. It of course has the largest available hard disk and RAM. Most people were pushing $4000 for a good system with printer. And laptops, note, were a sharp step up in price - nearly doubling - from desktops of similar horsepower.

And then here's eight years later than that PC and six years later than my

$12,000 fully-decked out XT. The Calgary Computer Paper back page, 1989.

Prices range from just under $2000, to just over $3000, with the at-the-time inevitable conspicuous consumption of the $7000 for the 33MHz machine just a third faster than the $3200 25MHz. It of course has the largest available hard disk and RAM. Most people were pushing $4000 for a good system with printer. And laptops, note, were a sharp step up in price - nearly doubling - from desktops of similar horsepower.

fullscreen

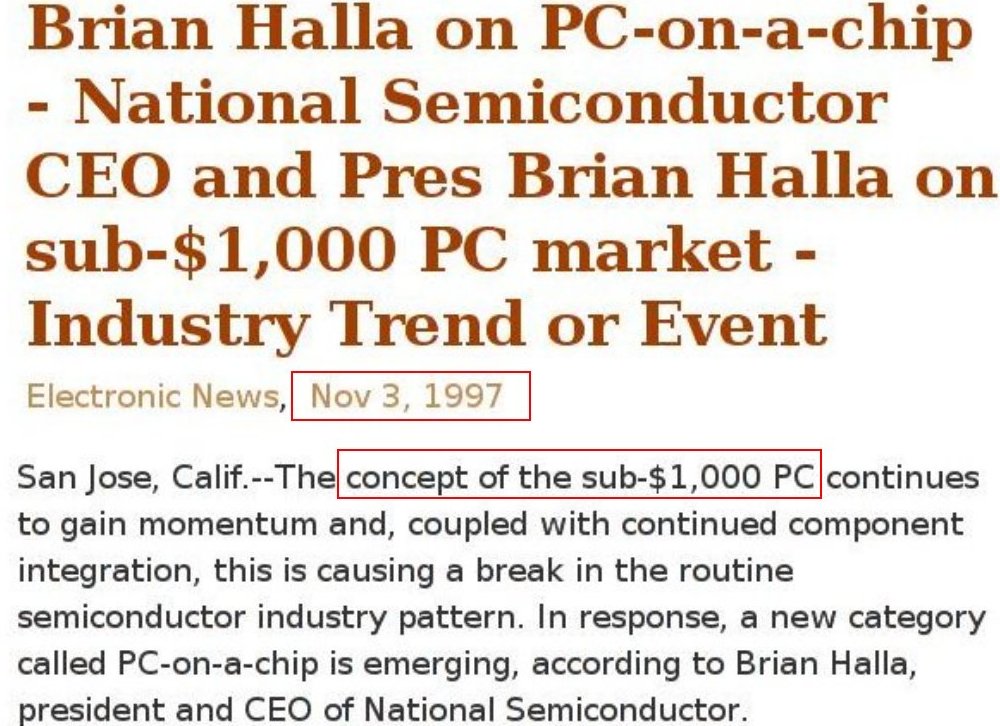

Flash forward another nine years and I find this end-of-1997 news story about the concept of the $1000 PC gaining momentum. Which I take to mean that some daring white-box factories in Asia were selling them like hotcakes to home users already. I think by 1998, it was a corporate offering. Of course, it's a marketing term - like $100 laptop - and most people were probably spending close to twice that for a step-up machine, like the real $188 laptop. So the common purchase size had dropped by about half.

Flash forward another nine years and I find this end-of-1997 news story about the concept of the $1000 PC gaining momentum. Which I take to mean that some daring white-box factories in Asia were selling them like hotcakes to home users already. I think by 1998, it was a corporate offering. Of course, it's a marketing term - like $100 laptop - and most people were probably spending close to twice that for a step-up machine, like the real $188 laptop. So the common purchase size had dropped by about half.

fullscreen

All right, another nine years takes us to this half-page in the Calgary Sun last week. Notice the ad format hasn't changed much in 18 years, it's a literary form like the murder mystery with a certain classic style. But also notice that none of the price numbers in the starbursts are four digits long - and the laptops and desktops are no longer so far apart, portability is only a slight premium now.

All right, another nine years takes us to this half-page in the Calgary Sun last week. Notice the ad format hasn't changed much in 18 years, it's a literary form like the murder mystery with a certain classic style. But also notice that none of the price numbers in the starbursts are four digits long - and the laptops and desktops are no longer so far apart, portability is only a slight premium now.

fullscreen

There's also been more compression between the "high end" and "low end" that made those genuine IBMs and Compaqs double the price of white boxes of similar guts. This is from last week's Dell ads; it's no longer the company it was, but these are still considered more reliable and better backed than the ones in the Sun ad, and they're nearly the same price points - again nothing over a thousand.

There's also been more compression between the "high end" and "low end" that made those genuine IBMs and Compaqs double the price of white boxes of similar guts. This is from last week's Dell ads; it's no longer the company it was, but these are still considered more reliable and better backed than the ones in the Sun ad, and they're nearly the same price points - again nothing over a thousand.

fullscreen

Indeed, a desktop equivalent to my current one at work is under $500. So I feel about right in claiming another halving.

Indeed, a desktop equivalent to my current one at work is under $500. So I feel about right in claiming another halving.

fullscreen

Even the conspicuous consumption page tops out at under 3 grand for their best laptop and under 2 for the gamer desktop - easily spotted by the sales pitched at that demographic: the RAM stick is brand-named "Corsair Dominator". My point here is that the common understanding of Moore's Law, if not quite backwards, is wrong to imply that the price we pay remains the fixed constant while the number of circuits alone varies. My 1982 professor stated as an axiom that "all chips cost $5", and that remains about true - but only manufacturers should care about that. Customers buy whole systems and there, the broad sociological consensus is that the generally popular purchase everybody has to go along with to "keep up", has taken only four-fifths of Moore's gains every decade: out of five doublings, we take greater power four times, and the fifth, we take as a price cut by half.

Even the conspicuous consumption page tops out at under 3 grand for their best laptop and under 2 for the gamer desktop - easily spotted by the sales pitched at that demographic: the RAM stick is brand-named "Corsair Dominator". My point here is that the common understanding of Moore's Law, if not quite backwards, is wrong to imply that the price we pay remains the fixed constant while the number of circuits alone varies. My 1982 professor stated as an axiom that "all chips cost $5", and that remains about true - but only manufacturers should care about that. Customers buy whole systems and there, the broad sociological consensus is that the generally popular purchase everybody has to go along with to "keep up", has taken only four-fifths of Moore's gains every decade: out of five doublings, we take greater power four times, and the fifth, we take as a price cut by half.

fullscreen

Remember it's Man that's the measure of all things, as shown here in the Da Vinci image with those measurements corrected for modern day America. It's really just kidding the talk about evil conspiracies of Andy Grove giving Power and Bill Gates taketh away. Big corporations may force us to upgrade, but over time customers force the market to their will. It's customer response that sets the agenda. People went along with the power needed for Windows and other GUIs, they wanted the power for computers to manipulate graphics, then sound, then video as they used to handle text; but they also slowly pushed prices downward. By price, again, I mean "the price of the typical, popular purchase at any given niche", be it corporate, home, student laptop, or gamer.

Remember it's Man that's the measure of all things, as shown here in the Da Vinci image with those measurements corrected for modern day America. It's really just kidding the talk about evil conspiracies of Andy Grove giving Power and Bill Gates taketh away. Big corporations may force us to upgrade, but over time customers force the market to their will. It's customer response that sets the agenda. People went along with the power needed for Windows and other GUIs, they wanted the power for computers to manipulate graphics, then sound, then video as they used to handle text; but they also slowly pushed prices downward. By price, again, I mean "the price of the typical, popular purchase at any given niche", be it corporate, home, student laptop, or gamer.

fullscreen

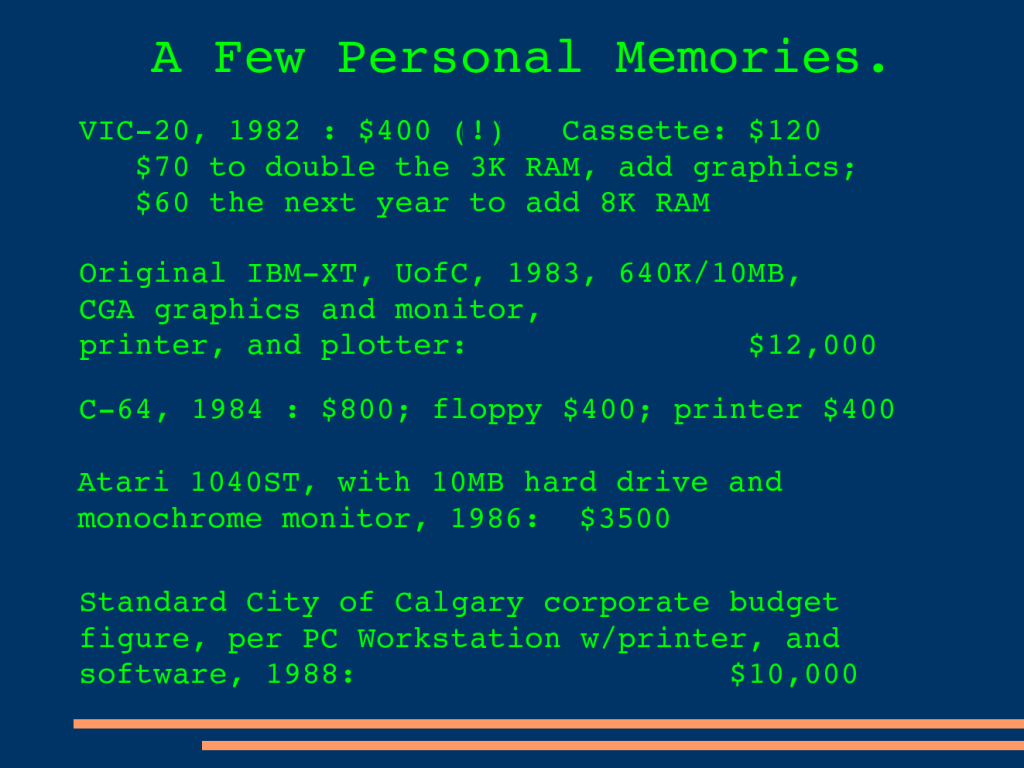

The real driver for these new cheaper, smaller laptops is flash RAM, which has

been shaking up the equations by following the old Moore's Law: it's been halving in price every year for several years, as shown in this 2006 graph from Infoworld. I think the 2007 prediction turned out about right. While the next few years won't quite be price-halvings any more, they do point to the EEE PCs successor having a 16GB hard drive by 2010, along of course with more speed, a bigger screen and more RAM. And if my rule-of-thumb is right, prices will have edged down a bit, probably to $300 and $350 where it is now $350 and $400.

The real driver for these new cheaper, smaller laptops is flash RAM, which has

been shaking up the equations by following the old Moore's Law: it's been halving in price every year for several years, as shown in this 2006 graph from Infoworld. I think the 2007 prediction turned out about right. While the next few years won't quite be price-halvings any more, they do point to the EEE PCs successor having a 16GB hard drive by 2010, along of course with more speed, a bigger screen and more RAM. And if my rule-of-thumb is right, prices will have edged down a bit, probably to $300 and $350 where it is now $350 and $400.

fullscreen

This is the price breakdown of the XO laptop - sorry for the small web gif blown-up - showing the remarkable invention of the new screen technology not only bringing the screen below $100, but throwing in the WiFi, camera and power system for $63.

Different parts come down at different rates, and it all depends hugely on market feedback: if tens of millions of these things do sell, the package price will drop quickly. There's no real reason to believe that $100 laptop boast will not come true in the near future, if not for the XO, then for whatever does take off in sales. More to the point, we already have one machine under $200, with many customers finding it useful, it seems Moore's will soon push machines more like my EEE PC down towards $200.

This is the price breakdown of the XO laptop - sorry for the small web gif blown-up - showing the remarkable invention of the new screen technology not only bringing the screen below $100, but throwing in the WiFi, camera and power system for $63.

Different parts come down at different rates, and it all depends hugely on market feedback: if tens of millions of these things do sell, the package price will drop quickly. There's no real reason to believe that $100 laptop boast will not come true in the near future, if not for the XO, then for whatever does take off in sales. More to the point, we already have one machine under $200, with many customers finding it useful, it seems Moore's will soon push machines more like my EEE PC down towards $200.

fullscreen

If you search on Google with the terms "DVD" "magic" and "price point", you find a general agreement that while consumer electronics may start to take off below $500, you really see universal adoption at $200 - where it's not a decision you have to think about for a while; it's subject to impulse buys, which is the psychology of most non-essential goods purchase. At $200, a product penetrates every market sector, down to the humblest households in the first world and the upper half of much of the developing world.

If you search on Google with the terms "DVD" "magic" and "price point", you find a general agreement that while consumer electronics may start to take off below $500, you really see universal adoption at $200 - where it's not a decision you have to think about for a while; it's subject to impulse buys, which is the psychology of most non-essential goods purchase. At $200, a product penetrates every market sector, down to the humblest households in the first world and the upper half of much of the developing world.

fullscreen

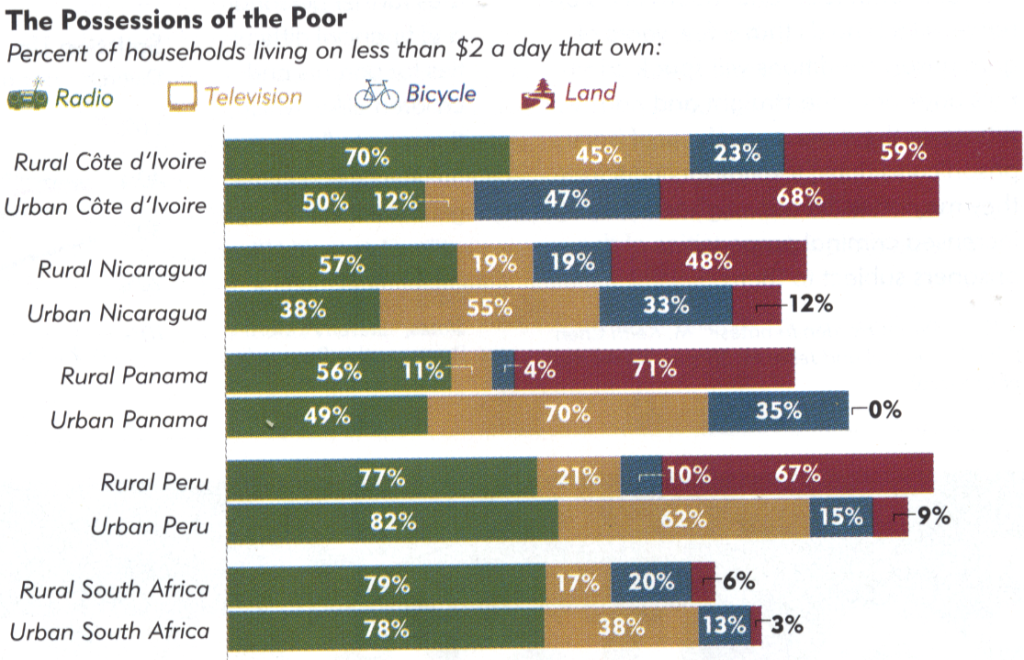

We hear a lot about people who make $1 a day, but Atlantic Magazine published surprising results of a survey of the purchases of the people who make $2 per day, enough to slowly save up tens and hundreds. We see a remarkable number of not only bicycles, but TVs, especially for the urban poor. There's a near-total penetration of radios, like 80% in rural Africa. The waiting market when the $200 first-world commodities hit the developing world, used and under $100, is literally in the billions.

We hear a lot about people who make $1 a day, but Atlantic Magazine published surprising results of a survey of the purchases of the people who make $2 per day, enough to slowly save up tens and hundreds. We see a remarkable number of not only bicycles, but TVs, especially for the urban poor. There's a near-total penetration of radios, like 80% in rural Africa. The waiting market when the $200 first-world commodities hit the developing world, used and under $100, is literally in the billions.

fullscreen

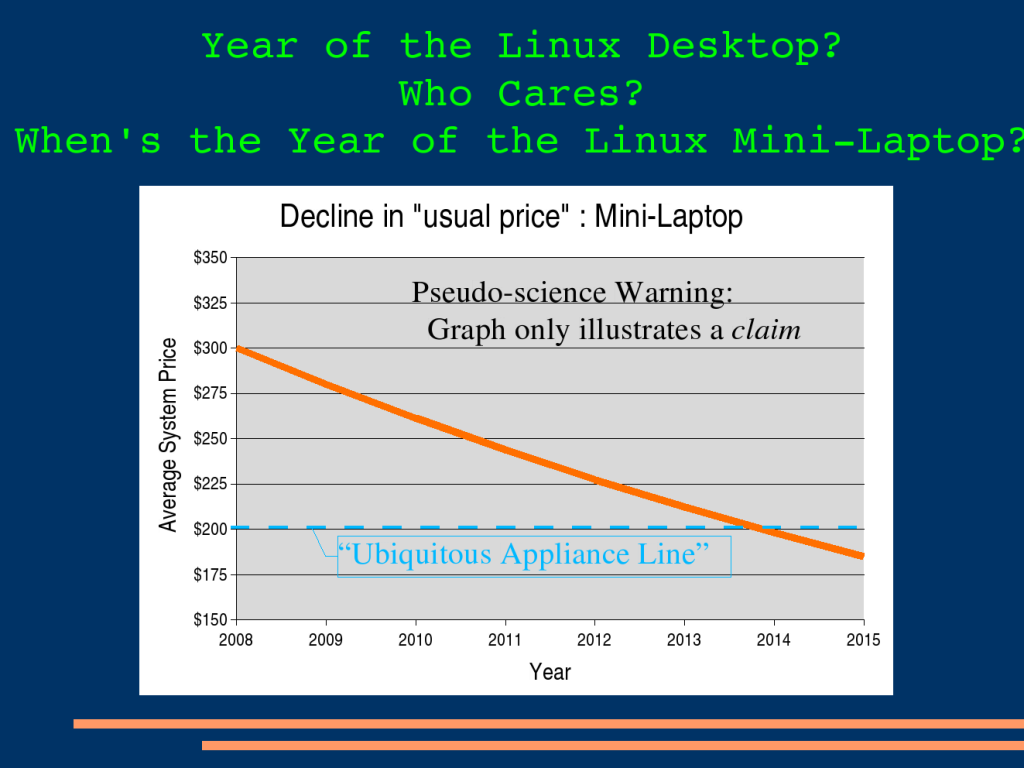

If my thesis is correct, customers will mostly let Moore's Law improve the specs of the mini-laptop they decide to buy and only slowly push the price down towards $200. But to give the process a head start, I'm going to assume the $400 I paid was an early-adopter gouge and that they'll be selling for $300 next year, because the story goes that they are already $250 in Japan. But at a rate of halving per 10 years, it'll be 2013 before $200 minis become the popular buy. Don't forget, however, that almost as many consumer electronics pundits think $300 is already the appliance price - so all through those years, the mini will be gaining soaring market share.

If my thesis is correct, customers will mostly let Moore's Law improve the specs of the mini-laptop they decide to buy and only slowly push the price down towards $200. But to give the process a head start, I'm going to assume the $400 I paid was an early-adopter gouge and that they'll be selling for $300 next year, because the story goes that they are already $250 in Japan. But at a rate of halving per 10 years, it'll be 2013 before $200 minis become the popular buy. Don't forget, however, that almost as many consumer electronics pundits think $300 is already the appliance price - so all through those years, the mini will be gaining soaring market share.

fullscreen

Which is presumably why Microsoft is now making Windows available on those Intel Classbooks for $3, with Office thrown in - and as part of it's "partnership" with OLPC is saying the XO should also run Windows. They believe that slim as the margins are in the under-$200 appliance market, they have to be in it, because it soon may be most of the market.

Which is presumably why Microsoft is now making Windows available on those Intel Classbooks for $3, with Office thrown in - and as part of it's "partnership" with OLPC is saying the XO should also run Windows. They believe that slim as the margins are in the under-$200 appliance market, they have to be in it, because it soon may be most of the market.

But I really don't see how they can manage the same kind of company in that environment. Their expected $50 per box is not going to work in the under $200 world. Under $5, maybe - and only if they deliver something the free software can't. With so many new customers piling in so quickly, customers who've never used any PC before, the old lock-in may not apply. Even if it has some effect, more than $5 is very hard to see. And that's gross - distribution costs would leave less room for profit.

So I believe that the under-$200 world is going to be as hard on Microsoft and similar software companies. Remember the transition from $100,000 very custom software for workstations and minicomputers towards shrinkwrap software under-$500on PCs? That was terminally hard on many software companies, and it will be like that.

In conclusion, sell your Microsoft stock now. And use it to buy a cheap little laptop - they're a hoot.